So how many giraffes do you think

there were on Noah’s ark? (By the way you don’t have to believe in Noah or his ark to answer this. It is a theoretical question. You only need some familiarity with the mythology.) I’m

asking because this is a question that pops up in my novella ‘The Year of the

Dugong’ and the answer sheds an interesting light on our knowledge (or lack of

it) of the natural world. Stay with me …

Start, if you can, by imagining an illustration of

Noah’s Ark – the kind you might find in a children’s book. Like the one I’m

using here. An artist with this commission is ridiculously spoiled for choice. There are a million

or so animals available to populate the picture. But since most of those million

creatures would be rather inappropriate for an ark – including fish, bugs,

worms, and myriads of sea-creatures, let’s limit the scope to land mammals, reptiles,

and flightless birds. This would offer around fifteen thousand pairs of animals

for our illustrator to choose for the ark. Yet despite this, you may have

noticed, one pair of animals nearly always makes an appearance – giraffes. No

respectable ark is complete without them. Just two of them. But here is the thing. Two giraffes are

not enough. There are, you see, depending upon whom you ask, either four, six,

or eight, or even nine different giraffes. Noah would have been remiss in his

duties if he didn’t take eighteen. You don’t often see eighteen

giraffes on Noah Ark. But perhaps you should.

It might surprise you to learn that a giraffe is not always

a giraffe – or rather that two giraffes randomly admitted onto an ark might not

necessarily be the same. We are used to using the one word, ‘giraffe’ to

describe them all. But that’s our laziness or our ignorance, not a recognition

of reality. The four species most zoologists agree upon are the Masai giraffe, the

northern giraffe, the reticulated giraffe (sometimes called the Somali giraffe),

and the southern giraffe. It isn’t all that difficult to tell them apart. The

reticulated giraffe, for example, has a rather distinctive pattern. It doesn’t

have spots. It has a kind of continuous, smooth, white line on a nutty brown, almost

orange background, creating large and slightly irregular polygons, like

something drawn by a graphic designer during a coffee break. The Masai giraffe

is a whole lot darker, and its pattern is blotchy. It has smaller markings that

are sometimes described as ‘star shaped’ but are more like the kinds of

explosion-shapes you get in comic books. The northern giraffe looks something like

the reticulated giraffe, but with smaller markings and a wider white line. You

can spot a northern giraffe because its pattern ends at the knee (which is not

strictly a knee, but you know what I mean). The southern giraffe is lighter –

often very pale – with spots on the lower legs.

And there could be more. There are zoologists out there who

insist that the northern giraffe is not one species, but three; these people

are cheerleaders for the Kordofan giraffe which lives in hard-to-get-to places

like Chad and the Central African Republic, the Western giraffe (mostly

confined to Niger), and the Nubian giraffe which lives in East Africa but isn’t

really happy there. Equally the southern giraffe might be two species –the

Angolan giraffe, and the South African giraffe. Which would give us eight.

This is all rather confusing, and somewhat unexpected. This

is the Twenty First Century after all. Surely, we know how many species of

giraffe there are? But no. It seems we don’t. The fact is, while zoologists can

get very worked up about identifying species, giving them names, describing

them in guide-books and so on, nature itself tends to get on with things in a

much more messy way, content to leave the cataloguing up to us. Most

dictionaries define a ‘species’ broadly,

or approximately, as ‘a group of living

organisms consisting of similar individuals capable of interbreeding,’ and

this is an important definition because the idea of a species is a fundamental

concept in biology, in the same way, perhaps, as an element is in chemistry, or

a date is in history. A species should be something with hard boundaries, about

which we can all agree. But take a look again at that definition. ‘Similar’ is a rather vague word to have

in a dictionary definition. Is a reticulated giraffe similar to a Masai giraffe? Well yes. Tourists might see both in

parts of Kenya and not be aware they’ve seen two different giraffes. But can

they interbreed? Now this is harder to establish. We know from studies of giraffe

genes that the four species described above have not exchanged genetic material

for over a million years. But this doesn’t mean they couldn’t. Maybe they have

been separated geographically for so long they haven’t had the opportunity to

try. Perhaps if Noah found two frisky, fecund giraffes – one reticulated and

the other, say, a Nubian – they might be persuaded to breed. This isn’t an

experiment we can readily carry out, and even if we could, there are powerful

ethical arguments that would (and should) prevent us. But even if we were,

somehow, to cross a Masai and a Nubian giraffe, it wouldn’t necessarily mean

they were the same species.

Consider the lion and the tiger. No one would dispute these

are different, very distinct species. Yet there exists an animal known as a

‘liger’ which is the offspring of a female tiger and a male lion. (A ‘tigon’ is

a similar thing where the parents are the other way around). Ligers and tigons

only exist in captivity, and no evidence has ever been found that lions and

tigers have ever interbred in the wild (even though their ranges cross in parts

of India). We know from genetic studies that lions don’t have tiger genes, or

vice versa. There was once an assumption that these liger and tigon hybrids would

always be infertile in the way that mules are (a mule is a cross between a

horse and a donkey), but this doesn’t seem to be the case. In 2012 a Siberian

zoo successfully bred a ‘liliger’ which is the offspring of a lion and a liger.

So where does this leave us? Are lions and tigers the same

species or not?

On 11th July 1978, shortly after nine in the

morning, a 22 year old Asian elephant called Sheba, who had been behaving

rather strangely, surprised her keepers at Chester Zoo in the north of England by

delivering a calf. The only bull elephant Sheba had encountered for well over

two years had been a rather temperamental African elephant known as Jumbolino

or ‘Bubbles.’ No one had expected an Asian elephant and an African elephant to

be able to interbreed. The calf, called ‘Motty’ (after George Mottershead the

founder of Chester Zoo), had ears like an African elephant, but just one ‘trunk

finger’ like an Asian elephant. A day later the baby elephant was on his feet

and bottle feeding, and within four days Sheba was feeding him normally. Sadly

he didn’t survive very much longer. He died of septicaemia aged just ten days,

but there is no reason to think he couldn’t have lived for very much longer –

perhaps even a full elephant lifespan.

As you’d expect, these are by no means the only animal

hybrids, or even the best known. The world of hybrid animals is characterised

by an apparent desire to mangle a name for the new creature out of the names of

the parents. So we have zeedonks

(zebra and donkey), jaglions (jaguar

and lion … although surely jagons

would be more conventional), grolar bears

(grizzly bear and polar bear), and even camas

(camel and llama). There was once a fashion for creating such animals, although

most zoos would look dimly on such an idea these days.

But perhaps the real surprise should not be that some

animals can be persuaded to interbreed, but rather that so few do, and

especially that this hardly ever happens without our encouragement. It seems

that the word species might need a

bit more definition. Perhaps we should redefine it as ‘a group of living organisms consisting of similar individuals capable

of interbreeding, and generally disinclined to breed with any other species.’

This is important because the whole idea of the species is

so fundamental to zoology. So while we are about it, shall we dispose of some

of the other words people often use when they try to talk about a species?

Let’s kick off with breed. I can’t

tell you how irritated it makes me when I hear someone call, say, a chimpanzee,

a breed of monkey. To begin with a

chimp isn’t a monkey – it’s an ape. More importantly a breed is something we humans

create. We breed dogs for hunting or for fetching or for pampering and the

resulting specimens we call a breed – cocker spaniels, German shepherds, French

poodles – these are all breeds. Throw them together and they would have no

hesitation in creating all manner of cross breeds, and these are breeds too

whether or not they are recognised and named by the Kennel Club or anyone else

for that matter. We have breeds of sheep, of cattle, of domestic cats, but we

don’t have breeds of giraffe or chimpanzees. While we’re on the subject of

breeds, we could throw in varieties.

I have heard this word used too when the speaker clearly meant species. You can

have varieties within a species. Some people have red hair, others are dark.

Some giraffes are taller than others. Variety is the motor for evolution, but

varieties are not taxonomically significant – which is to say they don’t affect

the way we classify or name animals or plants. Variety is often used by breeders to describe variations within a

breed, and they can be given names of their own – especially with plants. Any

competent horticulturalist can create new varieties of say, roses, by selecting

seeds with the characteristics they would like to see. Mix and match, and a

couple of generations later, hey presto, a rose named after your grandmother.

That’s a variety.

So having cleared that one up, let’s turn our attention to a

much more slippery word. In a park in Williamstown, Kentucky, about an hour’s

drive south of Cincinnati, you will find a very curious tourist attraction. Ark Encounter is a building designed to

look like … well, an ark, albeit an ark on land. Apparently built to the

dimensions provided in the book of Genesis, it’s aim is to convince us that

Noah was a real historical figure and his ark was a proper boat, and that,

guess what, he did indeed sail away in a flood with two of every kind of

animal, and there on board to help prove the point are models of hundreds of

animals including dinosaurs and even a couple of unicorns. But did you notice

the contentious word? Kind. This is

the word that enables Ark Encounter to get away without providing sixteen or eighteen giraffes, or six thousand snakes, or seven hundred thousand beetles. Their

website explains it like this: “Species

is a term used in the modern classification system. The Bible uses the term

“kind.” The created kind was a much broader category than the modern term of

classification, species.”

There. With a single judicious use of an ambiguous word

translated roughly by seventeenth century scholars in England from a seventh

century Greek translation of a bronze age Hebrew manuscript, Ark Encounter are

able to sweep away a thousand years of biological science. This is very

convenient for creationists. They no longer have to house loads of giraffes on

the ark. Two will do. A website called ‘Answers in Genesis’ goes even

further; it argues that the giraffes on the ark not only became the ancestors

of all of today’s giraffes, but also of okapis, and a host of now extinct

creatures. (That sounds suspiciously like evolution to me but let’s not be too

provocative.) The Answers in Genesis site goes as far as proving us with a

picture of what the giraffes on the ark might have looked like. They label the

picture ‘Shansitherium.’

There is no point really trying to argue with this. Creationists

will believe what they want to believe. But can the rest of us please agree

that the word ‘kind’ does not belong in any discussion of taxonomy. And while

we’re about it, can we dispose of another contentious word: race. Race

might once have been a useful (but informal) term in biology to describe a

genetically distinct population of individuals within the same species, but the

word has become hijacked by disagreements within our own species, so I would

suggest we set it aside completely. Along with the word ‘strain.’ There

may be races and strains of giraffes – there probably are – but I don’t imagine

even God expected Noah to collect every variation or every strain of giraffe on

the ark. If he had there wouldn’t have been room for anything else.

Now here’s another tricky word. Subspecies. The idea of

the subspecies can feel like a rather helpful way for zoologists to avoid

too many disagreements. We tend to call a group of animals a subspecies when we

find them in a different area with particular differences in size, shape, or

other characteristics, even though we might suspect that the different subspecies

can probably interbreed. You might have read about the imminent extinction of

the Northern white rhino. There are only two known individuals of this

subspecies still alive. Both are female, so sadly this is almost certainly the end for the

Northern white rhino. The two rhinos are called Najin and Fatu. They live in the Ol

Pejeta Conservancy in Kenya where they are protected by armed guards. When they

go it will undoubtedly be a great loss. But there is a sense that the loss of a

subspecies is less of a tragedy than the loss of a species. Northern and

Southern white rhinos have been living separately for at least half a million

years, but the differences that are visible to us are subtle, and you would

need to be an expert in rhino morphology to confidently tell them apart. There

may be other differences, of course, that are not visible, and

this might lead us to wonder if there are more rhino subspecies than the ones

we know. This could also be true of giraffes. Noah would surely have had quite

a challenge to untangle this. But the key point for us, and for Noah is this: if you have two subspecies that haven't interbred for half a million years, you do need to put both on the ark. Sorry. Remember that according to Bishop Ussher the flood that floated the ark was in 2349 BC, just 4,373 years ago - a blink of an eye in evolutionary terms. (Not really long enough by the way for a giraffe to evolve into an okapi but I did promise not to be provocative.) The IUCN (the International Union for the

Conservation of Nature) who are the arbiters of these things, officially recognises nine subspecies of giraffe. Here

they are in the illustration below (happily a royalty-free image: thank you

Alamy).

So the answer to our original question (memo to Mr Noah) appears

to be eighteen giraffes. We have to hope the ceilings on the ark were high.

But there is a

follow-on question. Why don’t we all know this? Why don't illustrators of the ark know this? Why isn’t this taught in schools?

How is it that we can identify soccer strips and car marques and fashion logos but we can

only collectively identify one giraffe? We knowledgeably and assertively distinguish

grape varieties and wine labels and cheeses and breeds of dog, but if you ask one hundred people

what species of rhinos still walk the earth, most, I fear, wouldn’t know. (There are

five, white rhinos, black rhinos, Indian rhinos, Javan rhinos, and Sumatran

rhinos). Why does this matter? Well if we can’t tell animals apart, we won’t mourn them when we lose them. That is why this matters. As Toby Markham says in 'The Year of the Dugong:'

"Do you know how many moths there are in Suffolk? How

many species? Probably over two thousand. And how many people do you think

could identify a single moth? Just one species?’ Toby raised a finger. He

paused to look at the silent crowd. ‘I doubt if one person in a hundred could

do that. So, if no one can identify even a single moth, how many people are

going to notice if two thousand species of moths become one thousand? Or one

hundred? How many people are really going to care?’

Natural history is becoming a dying art. That’s sad. I don't expect people to identify two thousand moths. But more people ought to know how many moths there are. Because if we don't care, then one by one they will surely go. And so will the Northern white rhino. And one day there may really only be a single species of giraffe. That's heartbreaking.

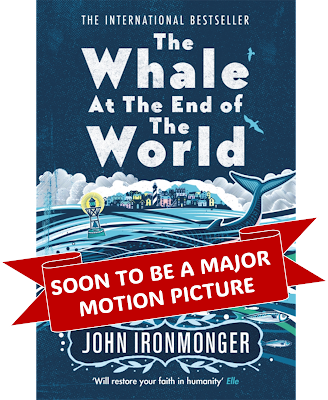

Check out my website: www.johnironmonger.com

.jpg)