John Ironmonger (author of 'Not Forgetting the Whale' - and other books) ... blogging about life, and travel, and books, and family, and writing, and Javan rhinos ...

The Wager and the Bear: COVER REVEAL 28 June 2024

Announcing the Polish edition of 'The Whale at the End of the World' 17 June 2024

How many giraffes were on the ark? (and other musings) [22nd April 2024]

So how many giraffes do you think there were on Noah’s ark? (By the way you don’t have to believe in Noah or his ark to answer this. It is a theoretical question. You only need some familiarity with the mythology.) I’m asking because this is a question that pops up in my novella ‘The Year of the Dugong’ and the answer sheds an interesting light on our knowledge (or lack of it) of the natural world. Stay with me …

It might surprise you to learn that a giraffe is not always

a giraffe – or rather that two giraffes randomly admitted onto an ark might not

necessarily be the same. We are used to using the one word, ‘giraffe’ to

describe them all. But that’s our laziness or our ignorance, not a recognition

of reality. The four species most zoologists agree upon are the Masai giraffe, the

northern giraffe, the reticulated giraffe (sometimes called the Somali giraffe),

and the southern giraffe. It isn’t all that difficult to tell them apart. The

reticulated giraffe, for example, has a rather distinctive pattern. It doesn’t

have spots. It has a kind of continuous, smooth, white line on a nutty brown, almost

orange background, creating large and slightly irregular polygons, like

something drawn by a graphic designer during a coffee break. The Masai giraffe

is a whole lot darker, and its pattern is blotchy. It has smaller markings that

are sometimes described as ‘star shaped’ but are more like the kinds of

explosion-shapes you get in comic books. The northern giraffe looks something like

the reticulated giraffe, but with smaller markings and a wider white line. You

can spot a northern giraffe because its pattern ends at the knee (which is not

strictly a knee, but you know what I mean). The southern giraffe is lighter –

often very pale – with spots on the lower legs.

And there could be more. There are zoologists out there who

insist that the northern giraffe is not one species, but three; these people

are cheerleaders for the Kordofan giraffe which lives in hard-to-get-to places

like Chad and the Central African Republic, the Western giraffe (mostly

confined to Niger), and the Nubian giraffe which lives in East Africa but isn’t

really happy there. Equally the southern giraffe might be two species –the

Angolan giraffe, and the South African giraffe. Which would give us eight.

This is all rather confusing, and somewhat unexpected. This

is the Twenty First Century after all. Surely, we know how many species of

giraffe there are? But no. It seems we don’t. The fact is, while zoologists can

get very worked up about identifying species, giving them names, describing

them in guide-books and so on, nature itself tends to get on with things in a

much more messy way, content to leave the cataloguing up to us. Most

dictionaries define a ‘species’ broadly,

or approximately, as ‘a group of living

organisms consisting of similar individuals capable of interbreeding,’ and

this is an important definition because the idea of a species is a fundamental

concept in biology, in the same way, perhaps, as an element is in chemistry, or

a date is in history. A species should be something with hard boundaries, about

which we can all agree. But take a look again at that definition. ‘Similar’ is a rather vague word to have

in a dictionary definition. Is a reticulated giraffe similar to a Masai giraffe? Well yes. Tourists might see both in

parts of Kenya and not be aware they’ve seen two different giraffes. But can

they interbreed? Now this is harder to establish. We know from studies of giraffe

genes that the four species described above have not exchanged genetic material

for over a million years. But this doesn’t mean they couldn’t. Maybe they have

been separated geographically for so long they haven’t had the opportunity to

try. Perhaps if Noah found two frisky, fecund giraffes – one reticulated and

the other, say, a Nubian – they might be persuaded to breed. This isn’t an

experiment we can readily carry out, and even if we could, there are powerful

ethical arguments that would (and should) prevent us. But even if we were,

somehow, to cross a Masai and a Nubian giraffe, it wouldn’t necessarily mean

they were the same species.

Consider the lion and the tiger. No one would dispute these

are different, very distinct species. Yet there exists an animal known as a

‘liger’ which is the offspring of a female tiger and a male lion. (A ‘tigon’ is

a similar thing where the parents are the other way around). Ligers and tigons

only exist in captivity, and no evidence has ever been found that lions and

tigers have ever interbred in the wild (even though their ranges cross in parts

of India). We know from genetic studies that lions don’t have tiger genes, or

vice versa. There was once an assumption that these liger and tigon hybrids would

always be infertile in the way that mules are (a mule is a cross between a

horse and a donkey), but this doesn’t seem to be the case. In 2012 a Siberian

zoo successfully bred a ‘liliger’ which is the offspring of a lion and a liger.

So where does this leave us? Are lions and tigers the same

species or not?

On 11th July 1978, shortly after nine in the

morning, a 22 year old Asian elephant called Sheba, who had been behaving

rather strangely, surprised her keepers at Chester Zoo in the north of England by

delivering a calf. The only bull elephant Sheba had encountered for well over

two years had been a rather temperamental African elephant known as Jumbolino

or ‘Bubbles.’ No one had expected an Asian elephant and an African elephant to

be able to interbreed. The calf, called ‘Motty’ (after George Mottershead the

founder of Chester Zoo), had ears like an African elephant, but just one ‘trunk

finger’ like an Asian elephant. A day later the baby elephant was on his feet

and bottle feeding, and within four days Sheba was feeding him normally. Sadly

he didn’t survive very much longer. He died of septicaemia aged just ten days,

but there is no reason to think he couldn’t have lived for very much longer –

perhaps even a full elephant lifespan.

As you’d expect, these are by no means the only animal

hybrids, or even the best known. The world of hybrid animals is characterised

by an apparent desire to mangle a name for the new creature out of the names of

the parents. So we have zeedonks

(zebra and donkey), jaglions (jaguar

and lion … although surely jagons

would be more conventional), grolar bears

(grizzly bear and polar bear), and even camas

(camel and llama). There was once a fashion for creating such animals, although

most zoos would look dimly on such an idea these days.

But perhaps the real surprise should not be that some

animals can be persuaded to interbreed, but rather that so few do, and

especially that this hardly ever happens without our encouragement. It seems

that the word species might need a

bit more definition. Perhaps we should redefine it as ‘a group of living organisms consisting of similar individuals capable

of interbreeding, and generally disinclined to breed with any other species.’

This is important because the whole idea of the species is

so fundamental to zoology. So while we are about it, shall we dispose of some

of the other words people often use when they try to talk about a species?

Let’s kick off with breed. I can’t

tell you how irritated it makes me when I hear someone call, say, a chimpanzee,

a breed of monkey. To begin with a

chimp isn’t a monkey – it’s an ape. More importantly a breed is something we humans

create. We breed dogs for hunting or for fetching or for pampering and the

resulting specimens we call a breed – cocker spaniels, German shepherds, French

poodles – these are all breeds. Throw them together and they would have no

hesitation in creating all manner of cross breeds, and these are breeds too

whether or not they are recognised and named by the Kennel Club or anyone else

for that matter. We have breeds of sheep, of cattle, of domestic cats, but we

don’t have breeds of giraffe or chimpanzees. While we’re on the subject of

breeds, we could throw in varieties.

I have heard this word used too when the speaker clearly meant species. You can

have varieties within a species. Some people have red hair, others are dark.

Some giraffes are taller than others. Variety is the motor for evolution, but

varieties are not taxonomically significant – which is to say they don’t affect

the way we classify or name animals or plants. Variety is often used by breeders to describe variations within a

breed, and they can be given names of their own – especially with plants. Any

competent horticulturalist can create new varieties of say, roses, by selecting

seeds with the characteristics they would like to see. Mix and match, and a

couple of generations later, hey presto, a rose named after your grandmother.

That’s a variety.

So having cleared that one up, let’s turn our attention to a

much more slippery word. In a park in Williamstown, Kentucky, about an hour’s

drive south of Cincinnati, you will find a very curious tourist attraction. Ark Encounter is a building designed to

look like … well, an ark, albeit an ark on land. Apparently built to the

dimensions provided in the book of Genesis, it’s aim is to convince us that

Noah was a real historical figure and his ark was a proper boat, and that,

guess what, he did indeed sail away in a flood with two of every kind of

animal, and there on board to help prove the point are models of hundreds of

animals including dinosaurs and even a couple of unicorns. But did you notice

the contentious word? Kind. This is

the word that enables Ark Encounter to get away without providing sixteen or eighteen giraffes, or six thousand snakes, or seven hundred thousand beetles. Their

website explains it like this: “Species

is a term used in the modern classification system. The Bible uses the term

“kind.” The created kind was a much broader category than the modern term of

classification, species.”

There. With a single judicious use of an ambiguous word

translated roughly by seventeenth century scholars in England from a seventh

century Greek translation of a bronze age Hebrew manuscript, Ark Encounter are

able to sweep away a thousand years of biological science. This is very

convenient for creationists. They no longer have to house loads of giraffes on

the ark. Two will do. A website called ‘Answers in Genesis’ goes even

further; it argues that the giraffes on the ark not only became the ancestors

of all of today’s giraffes, but also of okapis, and a host of now extinct

creatures. (That sounds suspiciously like evolution to me but let’s not be too

provocative.) The Answers in Genesis site goes as far as proving us with a

picture of what the giraffes on the ark might have looked like. They label the

picture ‘Shansitherium.’

There is no point really trying to argue with this. Creationists

will believe what they want to believe. But can the rest of us please agree

that the word ‘kind’ does not belong in any discussion of taxonomy. And while

we’re about it, can we dispose of another contentious word: race. Race

might once have been a useful (but informal) term in biology to describe a

genetically distinct population of individuals within the same species, but the

word has become hijacked by disagreements within our own species, so I would

suggest we set it aside completely. Along with the word ‘strain.’ There

may be races and strains of giraffes – there probably are – but I don’t imagine

even God expected Noah to collect every variation or every strain of giraffe on

the ark. If he had there wouldn’t have been room for anything else.

Now here’s another tricky word. Subspecies. The idea of

the subspecies can feel like a rather helpful way for zoologists to avoid

too many disagreements. We tend to call a group of animals a subspecies when we

find them in a different area with particular differences in size, shape, or

other characteristics, even though we might suspect that the different subspecies

can probably interbreed. You might have read about the imminent extinction of

the Northern white rhino. There are only two known individuals of this

subspecies still alive. Both are female, so sadly this is almost certainly the end for the

Northern white rhino. The two rhinos are called Najin and Fatu. They live in the Ol

Pejeta Conservancy in Kenya where they are protected by armed guards. When they

go it will undoubtedly be a great loss. But there is a sense that the loss of a

subspecies is less of a tragedy than the loss of a species. Northern and

Southern white rhinos have been living separately for at least half a million

years, but the differences that are visible to us are subtle, and you would

need to be an expert in rhino morphology to confidently tell them apart. There

may be other differences, of course, that are not visible, and

this might lead us to wonder if there are more rhino subspecies than the ones

we know. This could also be true of giraffes. Noah would surely have had quite

a challenge to untangle this. But the key point for us, and for Noah is this: if you have two subspecies that haven't interbred for half a million years, you do need to put both on the ark. Sorry. Remember that according to Bishop Ussher the flood that floated the ark was in 2349 BC, just 4,373 years ago - a blink of an eye in evolutionary terms. (Not really long enough by the way for a giraffe to evolve into an okapi but I did promise not to be provocative.) The IUCN (the International Union for the

Conservation of Nature) who are the arbiters of these things, officially recognises nine subspecies of giraffe. Here

they are in the illustration below (happily a royalty-free image: thank you

Alamy).

So the answer to our original question (memo to Mr Noah) appears to be eighteen giraffes. We have to hope the ceilings on the ark were high.

But there is a follow-on question. Why don’t we all know this? Why don't illustrators of the ark know this? Why isn’t this taught in schools? How is it that we can identify soccer strips and car marques and fashion logos but we can only collectively identify one giraffe? We knowledgeably and assertively distinguish grape varieties and wine labels and cheeses and breeds of dog, but if you ask one hundred people what species of rhinos still walk the earth, most, I fear, wouldn’t know. (There are five, white rhinos, black rhinos, Indian rhinos, Javan rhinos, and Sumatran rhinos). Why does this matter? Well if we can’t tell animals apart, we won’t mourn them when we lose them. That is why this matters. As Toby Markham says in 'The Year of the Dugong:'

"Do you know how many moths there are in Suffolk? How many species? Probably over two thousand. And how many people do you think could identify a single moth? Just one species?’ Toby raised a finger. He paused to look at the silent crowd. ‘I doubt if one person in a hundred could do that. So, if no one can identify even a single moth, how many people are going to notice if two thousand species of moths become one thousand? Or one hundred? How many people are really going to care?’

Natural history is becoming a dying art. That’s sad. I don't expect people to identify two thousand moths. But more people ought to know how many moths there are. Because if we don't care, then one by one they will surely go. And so will the Northern white rhino. And one day there may really only be a single species of giraffe. That's heartbreaking.

Check out my website: www.johnironmonger.com

The Wager and the Bear [Posted 29th Feb 2024]

SOON TO BE A MAJOR MOTION PICTURE 21 Jan 2024

One Step away from the Precipice: Climate Change in Fiction [Posted 20 Nov 2023]

This was my article yesterday in La Repubblica - Italy's biggest newspaper. The title translates as 'One Step from the Cliff' - and it is an artcle about climate change in fiction, and about my novel 'The Wager and the Bear' (Soon to be published in English I hope).

David Bowie had a remarkable

talent for writing songs that could conjure up a story. It is impossible to

listen to ‘Space Oddity’ without imagining Major Tom, sitting in a

tin-can, drifting forever into space.

But the Bowie song that stays with me most is ‘Five Years’. It tells

a very simple story. News has reached us that the earth has only five years

left. The planet is dying. In the song, the newsreader weeps. All around the

market square people lose their minds.

What would it be like, I have

often wondered, if we really were told this news? If a solemn news report,

backed by all the world’s serious scientists, was to tell us we were running

out of time? How would we react?

Well we now know the

answer to this question. Newsreaders wouldn’t weep. No one would go crazy. We

would ignore the danger and carry on with our lives as if nothing had changed. We

know this because this is what we do. Every few months the Intergovernmental

Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) produces a new report telling us the planet is

running out of time. Every year the COP climate change conference makes dire

predictions. Every year we learn that the previous year was the hottest on

record. We watch forest fires in Canada and Brazil. We see dramatic floods,

powerful storms, devastating droughts. We watch the collapse of animal

populations. World leaders fly in and out of conferences. They make vague

promises. But very little changes. And the world continues to die.

The challenge seems to be

a failure of human imagination. Perhaps it is the timescale. If the world was

doomed in just five years, we might be more alarmed. If it was an asteroid hurtling

towards us, we might make a real global effort to find a solution. But climate

change seems to be a long unfolding tragedy. We are like passengers in a

slow-motion train crash. The train is heading for a precipice, and all the

pieces are in place for a terrible disaster, but everything is moving so slowly

we stop worrying.

All this presents a

particular problem for story tellers. Climate change is the biggest story of

our time, yet very few novelists are ready to grapple with this. Ten centuries

from now, if humanity is still around, I suspect historians will only be

interested in one story from our generation - how we responded (or failed to

respond) to this existential threat to the planet. Science fiction, in general,

has done us rather a disservice here. Writers have sold us either Mad Max-style

desert dystopias, or impossible tales of starships taking survivors to new

green planets. What we don’t have are real world stories that could help us to

imagine the kind of earth we are creating. And that is a shame, because imagination is

what we need, now more than ever.

Once again, timescales seem

to be the challenge. Novelists need a central protagonist with whom readers can

identify. This character needs to have a story arc, and human dramas are

typically too short for climate change to feature very much. There is a second

problem too. It is hard to imagine any

character playing anything but a very minor role in what is a huge global

drama. No one is going to step forward like Bruce Willis and save the world. For

a writer, that is an unhelpful backdrop. We do not like to set up a jeopardy

for our characters, without giving them some way to fight back. But how do you

fight back against a warming planet?

In ‘L’Orso Polare e una

Scomessa Chiamata Futuro’ (The Wager and the Bear) I hope I may have found

a way to navigate a little around these two problems. The narrative unfolds

over a whole human lifetime, and the central characters are front-seat

observers of the climate disaster. The story involves two young men. One,

Monty, is a politician. He is a climate change-denier. He lives in a grand house

on the beach in Cornwall. He has a splendid lifestyle, and like so many of us

in the slow-motion train crash, he doesn’t see the precipice approaching. The

second man, Tom, is a climate scientist and campaigner. One drunken night, over

too many glasses of cider in the local inn, the two men get into a quarrel. It

ends with a deadly wager. In fifty years, either the sea will rise enough to

drown Monty in his home, or Tom will accept the jeopardy himself, and will walk

into the sea and drown. A video of the wager, posted online, goes viral. How

will it all work out?

Well we have fifty years

for the story to unfold. The lives of the two men cross several times, leading

them both onto a melting glacier, and ultimately onto an iceberg floating down

the coast of Greenland where their only companion is a hungry bear.

The story is not entirely

without hope. It is set against the backdrop of a campaign to restore some of

what the world has lost. Neither Monty nor Tom can save the world. But there is

at least hope, as well as despair.

Climate change doesn’t

have to be front and centre in contemporary fiction. But we shouldn’t be

ignoring it either. As writers we have a responsibility, sometimes, to make the

future seem real. We are hurtling towards a world of human-made disasters, of

dying oceans, of rising seas, of failing harvests, of droughts, of economic

collapse, and of climate-driven conflicts. We cannot ignore these things. If

these aren’t part of our fictional landscape now, then they need to be. Otherwise one day we may find we have just

five years left. And it won’t just be the news readers weeping.

Check out my website: www.johnironmonger.com

A brilliant but rather scary Italian cover for 'The Wager and the Bear.'

Check out my website www.johnironmonger.com

The Wager and the Bear (Der Eisbär und die Hoffnung auf morgen). [Posted: 27 April 2023]

The challenge with any story about climate change is to accommodate the long timescales. The climate catastrophe is something that might be almost instantaneous in geological terms, but measured against human lifespans it is ponderously snail-like. (See my last blog post https://notablebrain.blogspot.com/2023/04/climate-change-cats-and-spaghetti-essay.html) So unlike ‘Not Forgetting the Whale’ (Der Wal und das Ende der Welt) this story unravels over a whole human lifetime. And during this lifetime we will come to discover if Tom really is the hero and Monty the anti-hero. Or is it more nuanced?

I do hope, if you can read German, you will discover this book. If you do, please write to let me know your reactions. You can message me through this blog. If, like me, you are limited to reading in English you might have to wait a little longer. I suspect UK publishers want to wait to see how well it does in Europe – and this is because my last novel, ‘The Many Lives of Heloise Starchild’ didn’t sell all that well in Britain. My counter to this is to explain that ‘Heloise’ hit the bookshops in hardback when shops were closed due to Covid, and the paperback launched when bookshops were closed again. It launched with virtually no publicity. There was, I suppose, very little point publicising a book when the shops were all shut. So it goes. It had a beautiful cover – but (in my mind) the title was wrong. My original title was, ‘Katya’s Gift,’ and I can’t shake off the feeling that it would have done better with that title. Heloise is still my favourite novel by the way. And it is still out there if ever you’re looking for something new to read.

Anyway – all that aside, I can’t wait to see ‘The Wager and the Bear’ in print. Here again is that beautiful cover. And thank you once again to the wonderful people at S.Fischer Verlag for having faith in me.

Cats, and Spaghetti, and Climate Change [13 April 2023]

I can’t remember when (or where) I first heard the expression, ‘herding cats.’ I don’t think this idiom was around when I was young. So far as I can tell, it was invented sometime in the 1980s and it took off. Soon everyone was using it. It’s a great little saying because we all know enough about cats to understand right away what it means. ‘I did my best, but it was like herding cats.’ At once we appreciate the futility, the complexity, and the sheer absence of co-operation from everyone concerned. You don’t get herds of cats. They are too bloody-minded.

My father had a saying that meant almost the same thing. But

not quite. He would say, ‘it was like trying to organise spaghetti.’

Somehow, for me, organising spaghetti feels like an enterprise even more doomed

to failure than herding cats. The cats may not want to be herded, but there is

at least the possibility that they might eventually succumb. Spaghetti on the other

hand will never submit to organisation. And unlike the cats this isn’t due to wilfulness

or contrariness. Disorganisation is a property of the spaghetti itself.

Efforts to resolve the climate-change crisis are often

compared to herding cats. In this metaphor the ‘cats’ are the 195 countries on the

planet, across 7 continents, where no two countries think alike, or act alike,

or have the same priorities, or enjoy similar political systems, or possess the

same resources, or have the same levels of understanding. How do we ever herd

these slippery belligerent cats into the same box? Even so, I worry that the problem is more like

organising spaghetti. There is no way to do this. We’ll never get everyone on

board. Perhaps we ought to accept this and find a different way.

There is, by the way, a rather clever online tool called ‘Google

NGram Viewer.’ It can help you to figure out when (but not necessarily where) a

word or an expression arose. It searches millions of books over the past two

centuries, and if the words you’ve entered appear in 40 books or more in any calendar

year, it counts them and plots a graph to show how the frequency has changed

with time. Forty books feels like quite

a high bar to me. If you enter ‘herding cats’ you won’t find any use of

this expression until 1938. In 1942 the phrase disappears, and it doesn’t

reappear until 1987. After that the frequency graph rises meteorically, like

the lift-off of a space rocket. It is as if there was something that happened

in the Eighties that made this expression useful.

If, by the way, you try ‘organised spaghetti’ in NGram

Viewer you don’t get any results at all. Maybe this expression was exclusively

my dad’s.

If I look up from my keyboard, and glance out of my window,

I can see a storm coming. The clouds gathering over the estuary look as grey and

heavy as gunmetal.

And now, in the time it has taken me to type that last

sentence, the storm is upon us. The rain is driving against my window. I no

longer have a view. Funny how the weather

can do that, and we all accept it. We look at the forecasts and we plan our

days around them. Let’s do the beach on Sunday when the rain stops. But

if we’re told the whole global climate is changing, we go into a complex form

of denial. We don’t really know how to plan.

We hope that tomorrow will be much the same as today, and on the whole it is,

and that gives us comfort. It makes us think this is nothing to worry about. Yet.

One metaphor I have heard used about climate change is ‘a

slow-motion car crash.’ I used this myself in a novel, ‘The Wager and

the Bear.’ The image I wanted was of

an impending catastrophe where the parts are all in motion, where no one is yet

hurt, but where terrible death and destruction await if no one acts to stop it.

A slow-motion car crash seems to tick all of those boxes. But all the

same, I’m not altogether happy with this metaphor. For a start it seems too

prosaic. (I’m using the word prosaic to mean lacking in poetry – but also

to mean lacking in purpose.) I’ve tried to think of a better image. A train

crash is better perhaps, because it involves more people. But slow-motion is

insufficient to describe the slow and gradual increments of change that the

climate crisis delivers. Sea levels are rising by around four and a half

millimetres a year. In ten years, at this rate, they will rise four and a half

centimetres. And the sea, as we know, moves up and down, sometimes quite

erratically so that doesn’t feel like a threat. Not really. In a century the

sea might rise forty five centimetres. About knee high. And none of us likes to

think forward more than a century. Do we?

Isn’t that odd? We don’t have this blind spot with history.

We’re fascinated by the lives of the Tudors (Henry VIII was on the throne 500

years ago). We love stories about the Romans (2,000 years ago). And yet we don’t

speculate much on where our descendants might be in 500 or 2,000 years – what kind

of world they will inhabit. Or what (since we chose this measurement) the sea

levels might be. So let’s speculate then. Assume that sea levels keep on rising

at 4.5mm a year (in reality the rate will almost certainly accelerate but let’s

ignore that for a moment.) Our descendants in 2000 years will inherit seas 9

metres higher than today. The map of the world will have been altered

irreversibly. Britain will have lost most of East and Central London, and great

swathes of the Thames Valley including towns like Dartford, and Kingston.

Hundreds of seaside towns will have been wholly lost to the rising waters -

places like Portsmouth, Southampton, Middlesborough and Blackpool, Cardiff and

Newport, and Gloucester. Lincoln (now 38 miles from the sea) will be a seaside

town. So will whatever remains of Cambridge. So will York. So will

Taunton. Across The Channel most of the

Netherlands and much of Belgium will be underwater. So will huge tracts of Northern Germany.

America will lose thousands of communities down the Eastern seaboard. China will lose Shanghai and Guangzhou. Bangkok and Kolkata and Ho Chi Minh City will be gone. And Basra, Abu Dhabi and Dubai.

And here’s the thing. The water will still be rising. It

still has a way to go. If all the ice melts (and it probably will if global

temperature rises by 4 degrees) then sea levels rise seventy metres or so.

|

| 9 metres of sea level rise puts the Netherlands underwater |

And sea level changes are, perhaps, the least of our

worries. A 4 degree rise would make most of the world between the tropics practically

uninhabitable. It would certainly make agriculture almost impossible. It will cause

catastrophic drought . And the Northern farmlands which will now be warmer will

not take up the slack. Celestial mechanics will still restrict sunlight in

winter, and the soils are anyway very unproductive. And anyway a weird side

effect of climate change might mean that as the world gets hotter (and sea

levels keep rising) Europe curiously will get colder as ocean currents slow

down.

Finally there is a terrifying threat. This is how it might be in, 'The Year of the Dugong.' If atmospheric CO2 levels exceed 1,200 parts per million (ppm) (and they could) it could push the Earth’s climate over a tipping point. This would see clouds start to break up, and, a cloudless world will reflect away less sunlight. According to research published in the journal Nature Geoscience, this could trigger another 8°C rise in global average temperatures. Game Over.

So slow-motion train crash doesn’t work, does it? ‘Ultra-slow

motion asteroid-collision,’ might be better. A disaster movie that runs at

one frame a year. But the disaster is still going to happen. And it is inevitable

unless we can herd the unruly cats who govern us and get them to start

organising the spaghetti. Now.

Please check out my website for more information on my books. https://www.johnironmonger.com

More Movie Cliches ... [31 March 2023]

Back in January I wrote a blog post bemoaning lazy cliches in movies and on TV. https://notablebrain.blogspot.com/2023/01/movie-cliches-tropes-and-memes.html This, in turn, was prompted by an earlier blog post grumbling about the gun-related cliches in the new Avatar movie. https://notablebrain.blogspot.com/2022/12/avatar-2-and-all-american-love-affair.html

Well, as often happens, those posts got me noticing plenty more lazy cliches that movie makers use; so here, just for you, are a few of them. You’re welcome…

1. PSYCHO KILLERS ALWAYS PASTE THEIR BEDROOM WALLS WITH NEWS

CUTTINGS. When the cop finally stumbles into the lair of the serial killer/psycho

that’s how we know they’ve found the bad guy.

2. OLDER COPS ARE JUST ABOUT TO RETIRE. One extra case eh…

3. SENIOR COPS ALWAYS

BAWL OUT THE GOOD COP. This seems to be a rule. There is always a more senior

cop usually with a glass fronted office that looks over the incident room, and

he (or she) is NEVER pleased with the way the case is going, never says, ‘well

done,’ usually threatens to take the good cop’s badge, and generally pulls the

good cop off the case.

4. IF THE SENIOR COP ALSO HAS A BOSS, THAT BOSS WILL BE BENT

5. COPS NEVER CATCH ANYONE IN A CAR CHASE. Did you ever see a

car chase where the cops catch the guy they’re chasing, even if they throw a

hundred cars at it? No. The guy (who is being chased by cops usually because of

a misunderstanding) always gets away.

6. WRITERS ALWAYS WEAR SPECS. Also they either live in a cabin by a lake or in a New York apartment.

7. HEROES ARE NEVER HAPPILY MARRIED. Usually the wife has died.

Or else they’ve had an undeserved separation. Whatever, they are now available

but only reluctantly.

8. TEENAGE SONS ARE ALWAYS REBELLIOUS. If the hero dad gives

his teenage son an order, you know the son will flagrantly ignore it in the

next scene. But in the end the teenage son comes good, sees the errors of his

ways, and makes up with the dad.

9. TEENAGE DAUGHTERS ARE ALWAYS SUPER SMART AND USUALLY ABOUT TO

GO TO HARVARD.

10. DOCTORS ARE ALWAYS READY TO TELL YOU HOW LONG YOU HAVE TO

LIVE. AND IT’S USUALLY JUST SIX MONTHS. But protagonists with six months left

always look reasonably fit, they don’t spend the six months suffering in bed,

they get out there and fight the bad guys.

11. NIGHTCLUBS/SEEDY DIVES ALWAYS HAVE A STRIPPER IN THE

BACKGROUND, BUT NOBODY IS ACTUALLY WATCHING HER

12. IF A MOVIE STARTS WITH A HAPPY COUPLE MOVING INTO A NEW

HOME, YOU KNOW IT WON’T TURN OUT WELL.

13. IF A MOVIE INVOLVES A SINGLE PERSON MOVING INTO A REMOTE

CABIN IN THE WOODS, THEN DITTO.

14. MOTHERS AND DAUGHTERS WILL ALWAYS QUARREL

15. THE HERO COP/DETECTIVE WILL CASUALLY SPOT A CLUE THAT THE

WHOLE CSI TEAM HAVE OVERLOOKED. Hmm. I wonder who left this cigarette butt …

16. IF A SCENE TAKES PLACE IN PARIS, YOU WILL ALWAYS BE ABLE TO

SEE THE EIFFEL TOWER IN THE BACKGROUND OR THROUGH A WINDOW. In London it’s

usually Big Ben.

17. THE BAD GUY’S HENCHMEN DIE FIRST. Finally he’s the last one

left alive, but he’s also the trickiest to kill. Also, have you noticed;

henchmen never have any lines. No henchman ever has a wisecrack, or says

something poignant while dying. A shot henchman simply does the decent thing

and dies quickly and quietly. Also where does the bad guy find all these

henchmen? Are they amazingly well paid? Do they get paid holidays? Do they

grumble over their conditions of employment?

Why are they always happy to do as they are told even when it looks as

if they’ll die doing it? Why do they never say: ‘hey, this isn’t my fight.

Leave me out of it.’ And on that subject ...

18. HELICOPTER PILOTS EMPLOYED BY VILLAINS ARE STUPIDLY RECKLESS. Where do you employ a guy who is happy to fly a helicopter into such a dangerous situation that he and his helicopter will end up as a massive fireball? There must be an agency somewhere specialising in suicidal pilots ...

19. THE UNIFORM ON THE PEG/DEAD GUY IS ALWAYS A PERFECT FIT WHEN

SOMEONE ELSE NEEDS IT. We never see a character struggling to get into a stolen uniform. A side door just opens and out they step, dressed up. And amazingly no one will question them.

20. WHEN THE BAD GUY GETS HIS CHANCE TO KILL THE GOOD GUY HE

ALWAYS CHOOSES NOT TO. Why would you do that?

21. BIG PHARMACEUTICAL COMPANIES ARE ALWAYS EVIL. So are the

billionaire owners of social media and tech companies except for Stark

Industries

22. IT IS REALLY EASY TO KNOCK SOMEONE UNCONSCIOUS. If you’re

cool and you know how.

23. IT IS REALLY EASY TO KICK DOWN A DOOR. If you’re cool and

you know how.

24. IT IS REALLY EASY TO SNATCH A GUN OUT OF AN ANTAGONIST’S HAND.

If you’re cool and you know how.

25. IT IS REALLY EASY TO HACK INTO JUST ABOUT ANY COMPUTER. If

you’re uncool and a nerd hacker.

26. IT IS ALWAYS EASY TO PARK. There is always a convenient

space.

27. GIRL WAKES UP IN BED – WONDERS WHERE HER LOVER FROM THE

NIGHT BEFORE HAS GONE – DON’T WORRY – HE’S COOKING UP BREAKFAST. And actually

he’s an amazing cook. Who would have guessed?

28. IF THERE IS A POKER GAME – SOMEONE WILL ALWAYS HAVE AN

UNBELIEVABLE HAND. One protagonist has a once in a lifetime hand. But what do

you know. Someone else at the table has a better one.

29. IF THERE IS A CHESS GAME IN PLAY, IT IS ONLY EVER ONE MOVE

AWAY FROM CHECKMATE.

30. IT ONLY TAKES A SECOND TO PAY FOR A CAB. Movie people just

pass over a banknote and get out without speaking.

31. IF YOU CHASE ANYONE DOWN AN ESCALATOR AT A TUBE STATION,

GUESS WHAT? THERE WILL BE A TRAIN RIGHT THERE AT THE PLATFORM (OR JUST ARRIVING) FOR THEM TO HOP

ONTO. Yet whenever I run down an escalator at a tube station I find I just missed the train.

32. THE HERO ALWAYS MISSES HIS DAUGHTER'S BIRTHDAY PARTY / CONCERT. It isn't his fault. He'll be forgiven at the end.

I'm beginning to think this is an almost endless seam to be mined. If you've spotted any more lazy tropes, let me know, or drop them into the comments. I daresay I'll keep noticing them.

Please check out my website for more information on my books. https://www.johnironmonger.com

The Key to a Great Safari: A Great Safari Guide [9 March 2023]

|

| Paul Mbugua |

But what’s the alternative? Safaris are expensive. They’re

complicated. They don’t always go to plan.

Well I thought I knew the alternative. We were travelling with friends and that would spread the costs. I would plan our

safari myself. It would be way cheaper. I knew Kenya. I knew where I wanted to

go. So I googled safari lodges, and I read online reviews, and I worked out an

itinerary that would suit us. We’d do Nairobi National Park and the elephant

orphanage. We’d visit Lake Naivasha, and Crescent Island, and Hell’s Gate. We’d

stay at Lake Nakuru for the flamingos. We’d go on to the Masai Mara and we’d

spend time in the conservancies as well as the Mara Triangle. It would be

awesome.

And so I booked it. Six hotels/lodges. Twelve days. I flirted briefly with the idea of self-drive but

quickly abandoned it. I contacted Rhino Safaris because I trust them. I wrote

to Lacty, the owner, at info.nbo@rhinosafaris.net

. And I told him I needed a good safari land-cruiser and a first class guide

for ten days.

Readers – that is what we got. And it reminded me how

essential a great guide is for a good safari. Paul Mbugua was more than a first

class guide and an excellent driver – he was a splendid travelling companion

too. His knowledge of Kenyan wildlife and geology is astonishing. And

considering he was ferrying two smart-ass zoologists, and a geologist, including

one who felt he knew it all already (that would be me) he still had a whole lot

to teach us. Crucially he had enthusiasm. In spades. He would urge us to set

off early and return home late and it always paid off. Once we did two

back-to-back nine hour days and he never tried to rush us, or to set off before

we had seen what we wanted to see. He persuaded us several times to change our

agenda. Once was to break with the plan and visit Lake Elementeita. What a good

decision that was. Another time we swapped days around because he’d picked up

rumours of a leopard. Another good decision. His knowledge of every park was

amazing. And the only time we flummoxed him was when we told him we wanted to

visit Mount Suswa for the caves on the way back to Nairobi. Well, he’d never done

that trip before. So he hired a guide too. This time a Masai guide called Kiano

(kianosempui2018@gmail.com ) And

what a trip that was.

Nairobi: Was it right to go back? [3 March 2023]

|

| At Kenton ... |

|

| The Stanley |

|

| Nairobi |

Back in January I shared, on this blog, my anxieties about going back to Nairobi. ‘Never Go Back,’ was the advice so many people gave me. I grew up in Nairobi you see. I once knew every city street, and shop, and market stall. I was comfortable prattling in Swahili. I felt as if this city was part of my identity; somehow encoded into my very DNA. But fifty years have passed. I’ve lived in England since 1971. It’s a different time now. Hugely different. Someone warned me that the Nairobi I left was a city of half a million people; the Nairobi I was set to visit had five million. ‘Don’t go back was his advice.’

So did I do the right thing?

Memories are curious things aren’t they? If you live in a place

all your life, your recollections of that place evolve along with the landscape

as the years pass. But if instead, one day, you simply get up and leave, your

memories become frozen in time. Going back is like owning a precious vase, but alas,

the paintings on the vase are fading. Someone offers you a brand-new vase with

bright new paintwork. But if you accept it, you have to smash the old one. What

should you do?

Well of course, I went back. I smashed the old vase. (We

took a safari holiday with friends. I will blog about that sometime soon.) And guess

what? I didn’t regret a moment. Yes, it was strange. Embakazi Airport (Now Jomo

Kenyatta International) once the size of a high-school science block and comfortably

out of town, is now a huge complex bristling with dozens of airplanes and now

it is buried in a suburb of high-rise buildings, and the roads into town are

giant freeways and the traffic is terrible. But I found this exciting. Not

depressing. I knew the moment I stepped out of the plane I was going to love

this place. It was still Nairobi. (Perhaps that was the biggest surprise.) Lots

of the city is still absolutely recognisable. But even if it wasn’t, there is something

ineffable about this city, something I can’t quite describe or explain, that

stamps this place and its people with its mark and makes it simply the best and

most exciting city in the world. It’s a noisy, chaotic, colourful, amazing

place. Still. Thank goodness.

We stayed the first three nights at Masai Lodge – a safari

lodge in the National Park (a lovely place about an hour out of town. I’d recommend

it. Say hi to Cedric on the reception desk for me if you go there.) And we

stayed the last few nights at The Stanley. Good choices both. I’ve wanted to

stay at the Stanley all my life and it didn’t disappoint. And I visited my old

school (Kenton College) and had a very warm welcome there. It was emotional. I

watched a mixed-sex and multi-race group of kids doing football practice on the

very field where I once played (in an exclusively-white-male school), and it

brought a lump to my throat. I used my fifty year old memory to navigate

through the streets past the market and the University and the Norfolk Hotel to

the snake park (beware there is a new highway in the way) – and hey presto the

snake park itself is unchanged in almost every way. Even the black mambas are

in the same tank.

It was wonderful. It was cathartic. I left my fellow

travellers at the pool on our final afternoon and I took a walk around the city

centre on my own, and soaked up the magic and replayed my memories, and

relished all that was new and all that was unchanged. So yes – the old vase is

smashed; but I love the new one too. And my advice if you, like me, have been

away for too long, is very very simple. Go back. It’s wonderful.

Please check out my website for more information on my books. https://www.johnironmonger.com

|

| Unchanged - The Snake Park |

|

| Nairobi |

|

| Nairobi |

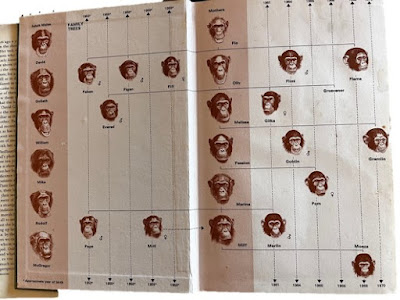

My Book Shelves (11): In the Shadow of Man by Jane Goodall [19 Jan 2023]

The first time I read Jane Goodall’s ‘In the Shadow of Man,’ I was studying zoology at university, and this was one of our course-books. I was expecting a dry, academic tome. What I discovered was the intensely personal autobiography of a young English woman and a detailed account of the family of chimpanzees that accepted her into their fold. It is a book that has never left me, and I have re-read it several times. One feature that makes In the Shadow of Man so compelling is the family-tree of chimp faces that appears on the flyleaf. It is impossible to read the book without regularly consulting this handy guide to the chimps in the troop. Goodall was twenty-seven when she started work at Gombe Stream National Park in Tanzania. It was 1960. For years she lived in the park, spending most of her daylight hours with the chimps. She is said, to this day, to be the only human ever to have been accepted into a chimpanzee group, and for almost two years she was the lowest ranking member of the Kasakela troop.

Almost every aspect of Jane Goodall’s work with chimpanzees

was pioneering when she started, and not always welcomed by the scientific

community. The idea that a researcher should live among a group of wild apes

was considered rather shocking, especially if the researcher was young, blonde,

and female. But Goodall’s most unconventional idea, perhaps, was to give her

chimps names. This annoyed traditional primatologists who accused her of

becoming emotionally attached to the animals. Today it is common practice for

zoologists to name animals, especially primates, and the names Goodall gave to

the Gombe chimps helped to bring their stories to a worldwide audience in a way

that would never have happened had they been Chimp A or Chimp B. I still

remember with affection the names of the chimps from In the Shadow of Man – David Greybeard, Goliath, Flo, Fifi, and

Flint.

|

| The Family Tree from In the Shadow of Man |

I've been working on a novel, on and off, that may or may not ever see the light of day. It draws heavily from 'In the Shadow of Man.' At present my title for this book is Girl/Ape. It is the entirely fictional story of a young woman who lives with a troop of wild chimpanzees. I'm 38 thousand words in; but who knows. I shall let you know how it goes.

Sue and I have been lucky enough to meet Jane Goodall twice on

her UK lecture tours, and both times her stories have brought us to tears. If

you want to learn more about Jane Goodall I heartily recommend In the Shadow of Man, along with ‘My Life with the Chimpanzees’ and ‘Through a Window: 30 Years with the

Chimpanzees of Gombe.’ You might

also like to subscribe to the Jane Goodall Institute’s YouTube channel.

Please check out my website for more information on my books. https://www.johnironmonger.com

My Book Shelves (10): The Asterix books by Goscinny and Uderzo [18 Jan 2023]

It is the year 50BC. After a long struggle, Gaul has been conquered by the Romans. All Gaul is occupied. All? No. One village still holds out stubbornly against the invaders…

And

there it is. The simple conceit that launched over forty books, a theme park, a film franchise, and one of the most enduring

partnerships in graphic literature – Asterix and Obelix – the

indefatigable (and indomitable) warriors of the little Gaulish village we have come to know so

well. If you’ve never encountered Asterix – where have you been? Surely no one can have escaped at least a

passing acquaintance with the books. In

a 1999 poll by Le Monde, 'Asterix the Gaul' was voted 23rd

greatest book of the 20th Century. And it isn’t even the best of the

canon. Not by a very long chalk. But it

was the first, published in 1959 (and in

English translation a decade later.)

|

| Some of my dog-eared Asterix books ... |

Where

do I begin to catalogue everything that makes the Asterix books such works of

unrivalled genius? They are funny, witty,

touching, and beautifully drawn. They mercilessly lampoon every national stereotype in

a way (and to an extent) you probably couldn’t get away with now. They are charming. Original. Clever. And above all

they are great stories.

But

I need to make an important distinction here. My unrequited love for these

books is limited to the first 24 volumes – those written by written by René

Goscinny and illustrated by Albert Uderzo (and translated by Anthea Bell and

Derek Hockeridge) until Goscinny’s death in 1977. These are:

1. Asterix the Gaul

2. Asterix and the Golden Sickle

3. Asterix and the Goths

4. Asterix the Gladiator

5. Asterix and the Banquet

6. Asterix and Cleopatra

7. Asterix and the Big Fight

8. Asterix and the In Britain

9. Asterix and the Normans

10. Asterix The Legionary

11. Asterix and the Chieftain's Shield

12. Asterix at the Olympic Games

13. Asterix and the Cauldron

14. Asterix In Spain

15. Asterix and the Roman Agent

16. Asterix in Switzerland

17. Asterix and the Mansions of the Gods

18. Asterix and the Laurel Wreath

19. Asterix and the Soothsayer

20. Asterix In Corsica

21. Asterix and Caesar's Gift

22. Asterix and the Great Crossing

23. Obelix and Co.

24. Asterix in Belgium

I give you below, the opening page of Asterix in Spain. If you can show me a better opening page of any book, I should like to see it.

Please check out my website for more information on my books. https://www.johnironmonger.com

My Publication Journey : (not so much a journey – more of a donkey ride). 28 May 2025

My lovely publisher Fly on the Wall Press asked me to write a short piece on 'my publication journey.' Here is the piece I sent the...

-

Up river in Ujung Kulon looking for Javan Rhinos ... I'd be the first to admit that Indonesia isn't exactly a top destination o...

-

[ This was posted to my blog on 12th February 2020 when we were only just beginning to hear about Coronavirus - just in case you wonder why...

-

This gorgeous cover-design is for my novella, ‘ The Year of the Dugong’ (Das Jahr des Dugong )’ due to be published in German on October 2...

-

At Kenton ... The Stanley Nairobi Back in January I shared, on this blog, my anxieties about going back to Nairobi. ‘Never Go Back,’ was the...

-

What is it like to hear someone read your writing aloud? I don't think I'd ever had that experience before. Not really; not read...

-

Perhaps I shouldn't admit to this. Maybe I should post a youthful photo and pretend to be thirty five. Oh dear. This is harder than I th...

-

Lava flowing into the sea I really should have consulted a map. But I'll blame the guidebooks all the same. They all say that Krakato...

-

Orang A village on the Sekonyer river A Klotok Proboscis Monkeys Enough of books and book prizes and the stresses and ...

-

Never go back. I’ve been given that piece of advice plenty of times, by lots of different people, but always with reference to one partic...

.jpg)

.jpg)